As a boy, he loved the harmony of nature and found that winning doesn’t always come to the person with the biggest stick

Nearly a hundred years ago, a boy grew up in a small village of colourful huts, shaped like round beehives, in a green valley near the southernmost tip of Africa.

From the age of 5, he would look after his family’s cows and sheep out on the grassy hills around the village.

His parents had given him the name Rolihlahla. Maybe they saw something in his future. Because the name means “troublemaker”. He would cause a lot of trouble –for people with bad ideas!

The boy learned how to live happily with the nature all around him – falling in love with the wide, blue sky, gathering fruit, or honey from wild bees.

He had fun swimming in cold streams or sliding down smooth rocks that his friends called their “roller-coaster”. They didn’t need to go to a theme park!

Stick-fighting boy

It wasn’t all just fun. The family had to eat, and little Rolihlahla learned to hunt. He killed birds using a slingshot – just a piece of leather that helped him throw stones really fast. And he caught fish with hooks he made himself.

A favourite game was fighting with sticks. He learned that winning wasn’t about being the biggest or the strongest – or having the biggest stick. He had to work out what the other person would do next – and to know what his own advantages were.

He learned something else, too. That would be important when he grew up.

One day, friends were taking turns to try and ride a donkey in the village. The animal got grumpier and grumpier. By the time Rolihlahla clambered on its back, the donkey had had enough. It ran a few steps, then stopped hard, pitching our hero face-first into a prickly bush. How his friends laughed at him!

Rolihlahla felt humiliated. He’d been made to look silly. That hurt more than a scratched face and bruised knees. From then on, he himself tried never to embarrass other people. For example, when he won a fight, he would say that his opponent had fought well. He knew that laughing at them would hurt them so much that they would always want to get back at him.

Becoming Nelson

The clever boy was sent away to school, to learn more than he could in the village. There he had to speak English, not his family’s language, called Xhosa.

His first teacher gave Rolihlahla a new, English, name. She called him Nelson. Nelson Mandela.

Though he learned from books, he also learned by watching. For example, he observed the people of his tribe debate important matters for their community. Everyone was listened to, he saw. They made decisions that were OK for everyone – it’s called consensus– so no one felt humiliated or forced into doing something just because most of the other people had a different point of view from them.

Nelson’s cleverness helped him get to university. He didn’t always work hard, and he got in trouble sometimes. He learned a new sport – boxing. Like in stick-fighting, he learned that in boxing, too, it was important to understand your opponent, to not waste your strength, to be patient and to choose the right moment to hit back.

Black and white issue

Nelson was unusual at university because he had black skin. Most people in Africa have black skin. But in Nelson’s country, South Africa, a small number of people with white skin owned nearly everything. Their families had come from Europe and they mostly spoke English or a kind of Dutch called Afrikaans.

Nelson became a lawyer to help defend poor, black people. He organised demonstrations, especially when the government introduced a new set of laws to keep power and money in the hands of “whites”.

These laws were called “apartheid”. It means apart-ness in Dutch. It was against the law for white and black people to fall in love. “Blacks” couldn’t use things that were for “whites only” – shops, say, or buses or beaches or even park benches. Many people, of course, weren’t clearly black or white. There were rules for them, too.

Fighting back

Nelson and his friends organised demonstrations. They copied how Indians had just won their freedom from Britain by peaceful, or non-violent, protests led by a man called Mahatma Gandhi.

But in South Africa, the government didn’t listen. They banned demonstrations and police killed many protesters. Nelson got impatient. With friends, he decided to use some violence to hit back. They tried not to hurt people but tried to make life difficult for the white government by blowing up things like electricity lines.

Before long, police found Nelson. He was put on trial. There, he did not deny what he had done but said it was the apartheid government that were the criminals.

He said he was against whites having all the power, but also against blacks having it. He fought to create a country where “all people will live together in harmony”.

Learning in prison

The judge sent him and his friends to prison for life. For many years, Nelson hardly saw or heard from his family. The government wanted people to forget about him.

It was hard. But Nelson was patient. And like a clever boy fighting with sticks or boxing, he used his time to learn more about his opponent.

The white guards on the prison island all believed in apartheid. Nelson learned to speak their language, Afrikaans. He learned about the hopes and fears of his guards and their families. Many guards came to like him and tried to help him in small ways, like getting him paper and pens, so that he could write.

“Help us”

For nearly 30 years, as Nelson grew old in prison, South Africa got worse. There was more violence and white-owned companies were struggling. Rich countries abroad stopped doing business with South Africa to protest against apartheid.

Eventually, the government came to Nelson and asked for his help. They would let him out if he would help them win back international business. He said ‘no’.

Nelson said he would only help if they gave black people and everyone in South Africa the same rights and held free elections. He knew his own strengths, even though the government had tried to weaken him by all those years in prison.

Shoelaces

For one of his first meetings with the white president of South Africa, they let him change his prison clothes for a suit and tie and proper leather shoes.

As the meeting was about to start, an assistant knelt down to tie Nelson’s shoelaces. He had been wearing prison sandals so long that he had forgotten all about shoelaces, and how to tie them! But he hadn’t forgotten how to win a fight.

Not revenge, but a rainbow

The white government finally agreed to give everyone a vote and let Nelson and all his friends out of prison. Many whites were terrified – that black people would take their revenge, try to kill them and take away their homes. Many blacks wanted to.

But even after spending nearly half his life in prison, Nelson didn’t let that happen. He stuck to what he said to the judge, that he wanted all South Africans, of all colours, to live in peace together. He declared that it would be the rainbow nation.

Childhood lessons

Nelson never forgot what he learned as a boy in the countryside, a boy called Rolihlahla, who knew about all the different parts of Nature living in harmony.

“It was in the fields that I learned how to knock birds out of the sky with a slingshot, to gather wild honey and fruits and edible roots, to drink warm, sweet milk from the udder of a cow, to swim in the clear, cold streams, and to catch fish with twine and sharpened bits of wire.”

Nelson mandela

He didn’t forget what he learned when he fell off the donkey into the thorn bush and the others laughed at him – the lesson about not humiliating your opponent.

He didn’t forget his people, who had suffered for many years. But he also didn’t forget what he learned from his prison guards, who also wanted to live in peace.

Making peace

Many black people were amazed that, after they elected Nelson Mandela the president of South Africa, he appointed not just blacks to help him but also some of the white men who had helped keep him in prison all that time.

Nelson explained that we shouldn’t forget the past. But that if we don’t make peace with our opponents, then we are trapped in the past and can never stop fighting.

Nobel Peace Prize

His life and his ideas make Nelson Mandela one of the most famous people to win the Nobel peace prize. And as we spend our WoW! summer preparing to mark the International Day of Peace on September 21, his story is a great way to start our series on ‘peacemakers’, which will continue next month.

Nelson Mandela achieved extraordinary things (although he himself always said he was just an ordinary man who made mistakes but tried to do his best in hard times). But we can all be peacemakers in our own everyday lives, too.

Can you think of something you’ve learned about Nelson that you could use yourself? Perhaps about listening to other people? About taking time and being patient?

If you’ve enjoyed learning about Nelson, look out for the next story in our summer series. And to tell your friends about us!

Did you know?

Apartheid was a horrible system and seems crazy to us now.

Imagine this: if you had brown skin, they might not be sure if you were legally black. So they did the pencil test. They put a pencil in your hair and made you shake your head. If the pencil didn’t fall out, it meant you had tight curly hair like most Africans – and so you were counted as “black”…

Problem?

Nelson Mandela patiently and peacefully pushed South Africa’s white government to give black people equal rights. But when it did, many people were afraid of a war between some white people who were against the change and some black people who wanted to take white people’s homes and make them leave the country.

Solution!

Nelson Mandela persuaded people to come together as “the rainbow nation”. As a boy, he had learned not to humiliate a defeated opponent and held out a hand to whites*. In 1993, he shared the Nobel Peace Prize with the last white president of South Africa. The following year he was elected as the first black president.

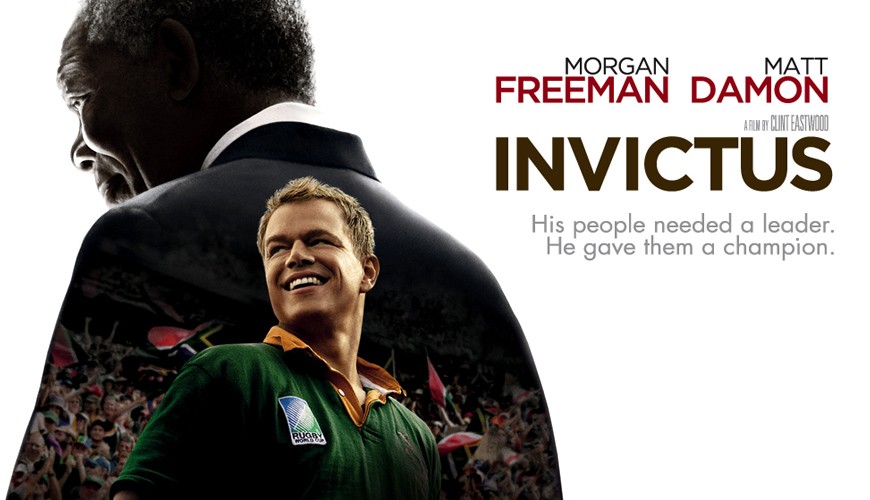

* In this historic photo, President Mandela presents the 1995 Rugby World Cup to the captain of the South African team. Historically, rugby was mainly played by whites and most black South Africans ignored the national team, called the Springboks. But Mandela encouraged the “rainbow nation” to support them. And he wore a Springbok jersey to present the Cup!

Grown-ups’ follow-up

This is the first of three portraits of “great peacemakers” we are running fortnightly over the holidays ahead of the International Day of Peace on Sept. 21. We have partnered with the French branch of the Jane Goodall Institute and their global youth movement Roots & Shoots to show children how making peace is something everyone can do. Read our story here!

There’s no shortage of material about Mandela online. This Canadian obituary after his death in 2013 aged 95 is eloquent.

For more detail about Mandela’s recollections of his childhood on the South African veldt, you can dip into his autobiography, A Long Walk to Freedom, here.

There are some excellent resources specifically for kids on the website of the World Children’s Prize, of which Mandela was a patron. Take a look at this graphic novel about Mandela’s life, called The Black Pimpernel or its first-hand accounts for children of what life was like under racist laws Children Under Apartheid.

To learn more about how Mandela used the 1995 Rugby World Cup to try and heal divisions, the 2009 film Invictus, starring Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon, makes great family viewing. If you subscribe to Netflix, it’s available free at the moment.